Hawai‘i’s Post-COVID Recovery Plan Puts Women First

It may be too soon to reopen, but it’s not too early to plan for a recovery. The novel coronavirus pandemic continues to spike in many U.S. states, especially those that lifted lockdown restrictions early, but as of July 6, Hawai‘i had only 72 cases per 100,000 people, the lowest in the nation.

Instead of resting on those laurels, Hawai‘i also has developed the most comprehensive post-pandemic recovery plan, one that includes feminism as a core principle.

Released in April 2020, “Building Bridges, Not Walking on Backs” is a substantial plan that advocates for improving the lives of women to spur a post-pandemic economic recovery.

This is a manifestation of the women’s movement in Hawaiʻi.

The plan is intersectional and comprehensive, offering recommendations on everything from rectifying the gender pay gap to using federal loans to bolster critical social services, such as domestic abuse shelters and reproductive health care.

“I think it’s really important and pretty exciting,” says Noelani Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, a professor of Native Hawaiian politics and Indigenous feminism at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. “I don’t know of any other feminist-centered plans for recovery that have been put out anywhere. Not just in Hawai‘i, but in other parts of the world.”

In America, many states are prioritizing reopening and personal freedom over public health and safety—and now reversing those decisions. Few are working towards establishing a new, more equitable post-pandemic normal for vulnerable communities.

Hawai‘i is doing just that. First, the state has taken a comparatively conservative approach to reopening, according to the Los Angeles Times.

As in many colonized nations, the repercussions of colonialism in Hawai‘i extend to the present.

At the same time, Hawai‘i’s legacy of partnerships across the public, private, and citizen sectors is helping keep the concerns of Native Hawaiians and women front and center of the post-coronavirus planning.

“This is a manifestation of the women’s movement in Hawaiʻi,” said Khara Jabola-Carolus, executive director of the State Commission on the Status of Women about the plan. “I’m an anti-imperialist feminist. I am a transnational feminist, and I’m also a bureaucrat. I get to occupy this space because I had built up a sisterhood around me and that sisterhood existed before me, built by other women.”

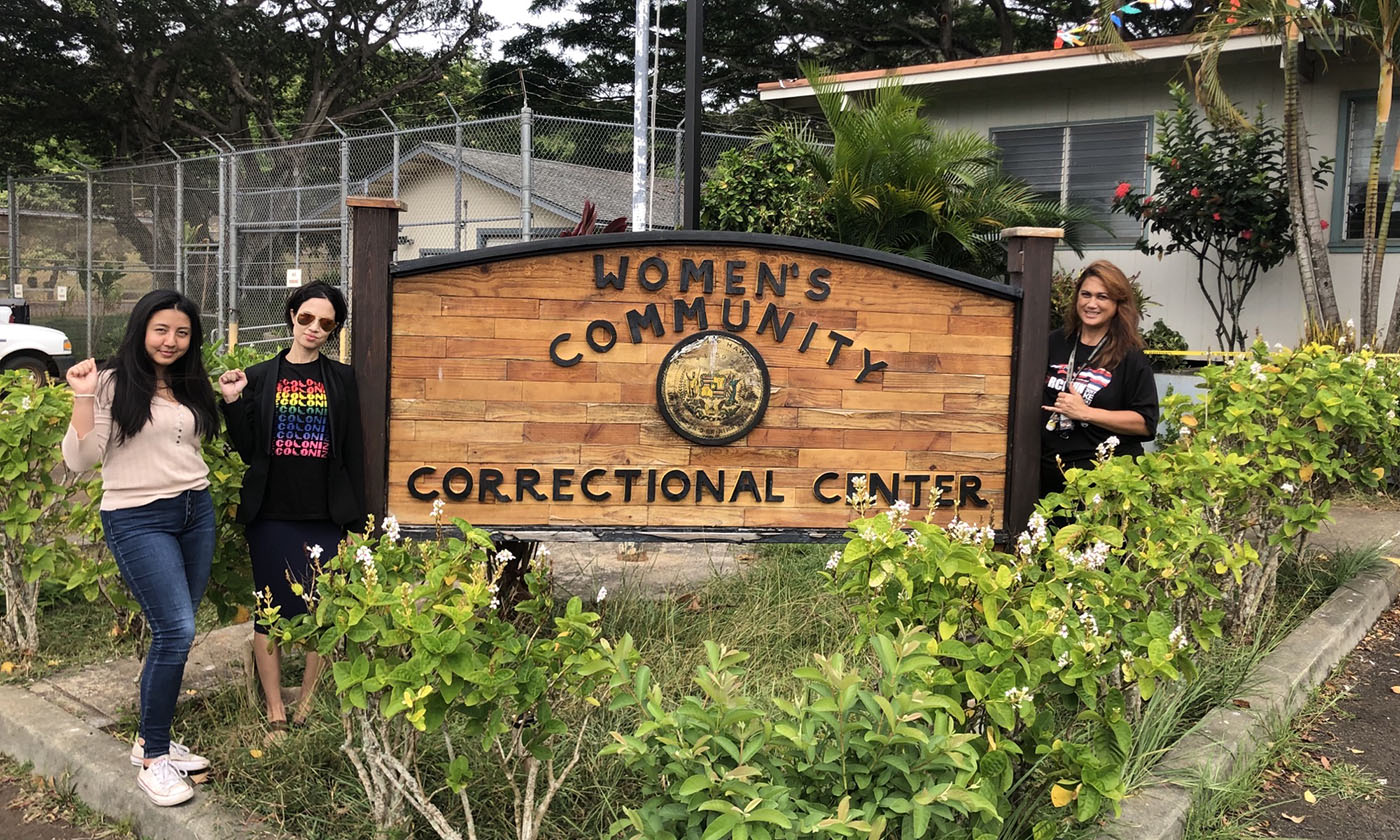

The commission was organized in 1964 and, bucking the norm of public agencies having antagonistic relationships with activists, has routinely interacted with grassroots organizations such as the local chapter of AF3IRM, a group that was involved in shaping the recovery plan. Two activist groups, the Micronesian Women’s Taskforce and Healthy Mothers Healthy Babies, also contributed to the project among other experts.

“They restarted the women’s movement in Hawai‘i,” Jabola-Carolus says. “It’s really unique because it’s Native and immigrant women in one organization together working across political tensions and working through intersections. You don’t often see that.”

She intentionally invited people outside of professional advocacy, especially those whose working status or educational attainment traditionally keeps them from engaging in policy formation and implementation.

United under the moniker “Hawai‘i Feminist COVID-19 Response Team,” and functionally a part of the state commission, the group swelled to about 40 members and is still recruiting.

The team edited the document collaboratively, a way to “see democracy in real time and have people weigh in,” Jabola-Carolus says.

The document reflects this multiplicity of voices. For example, it suggests leaning into “subsistence living and the perpetuation of land- and sea-based practices traditional to Hawai‘i’s ecological and food system” to catalyze economic growth, as opposed to tourism, which, according to the plan, offers only low-wage jobs, is linked to rights abuses and contributes to environmental degradation.

This moment really forces a conversation about how to diversify Hawai‘i’s economy away from tourism and the military.

The recovery plan also has provisions for commercial sex workers, members of the LGBTQ community, and caregivers, groups whose already-precarious social and financial situations have been exacerbated by the virus.

“A lot of women … are seeing themselves as an oppressed class right now that didn’t before,” Jabola-Carolus says. “Womanhood is a caste. Being femme or nonbinary and having all these extra duties is personally and structurally oppressive.”

As in many colonized nations, the repercussions of colonialism in Hawai‘i—which culminated with an 1893 coup backed by U.S. and European business interests that overthrew Queen Lili‘uokalani—extend to the present.

“There is a lot of tension,” Jabola-Carolus says. “Hawai‘i is a settler-colonial state… it’s just a constant battle to make sure our communities are not erased.”

Colonial involvement led to the economy becoming overdependent on certain revenue streams, first the exporting of sandalwood and sugar, then in the post-war era, tourism, and the U.S. military.

Rethinking equity in Hawai‘i is also timely in the context of worldwide George Floyd protests and subsequent demands to reform the police.

Before the COVID pandemic, tourism accounted for nearly a quarter of the state’s gross domestic product, while the “defense economy” represents $7.2 billion in spending annually, about 8% of GDP. Both industries are problematic in and of themselves; so is relying so heavily on just two revenue streams, the writers of the recovery plan argue.

“[T]his moment really forces a conversation about how to diversify Hawai‘i’s economy away from tourism and the military [which have been] dominant to the point of really kind of choking out other aspects of the economy here,” Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua says. “[B]oth industries have incredibly patriarchal and exploitative and violent aspects…”

Indigenous Hawaiians have the highest poverty level of all of Hawai‘i’s five largest ethnic groups. And an estimated 15,000 people are homeless in Hawai‘i, the highest per capita rate in the country.

“[I]n places like Hawai‘i, [the virus is] exacerbating what was already deep inequity,” says Kealoha Fox, a Native Hawaiian clinical psychologist and member of the recovery team. “Hawaiʻi has this stereotype… that we are the best state to retire [to], we are the healthiest state in the country, we have the best resorts, and you can come here and be happy. It’s like Disneyland for adults. But that’s not true for everybody who lives here…”

Native Hawaiians are very heavily impacted by the criminal justice system.

Rethinking equity in Hawai‘i is also timely in the context of worldwide George Floyd protests and subsequent demands to reform the police. In Hawai‘i, Black people make up just 2% of the population, and Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders suffer disproportionately from overpolicing and incarceration.

“It’s also a really great moment to be thinking in the terms that [the recovery team is], intersectionally, about their future, their feminist analysis with the rise of the current uprising of Black Lives Matter and thinking of policing and the criminal justice system,” Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua says. “[B]ecause, in Hawai‘i, it’s a situation where Native Hawaiians are very heavily impacted by the criminal justice system.”

But the fact that the plan is intended to shape these sorts of state policies means it has to have some limitations, Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua says.

Issues of land rights, self-determination, and sovereignty, all of which relate to a larger discussion of how Hawaiʻi can be more autonomous from the rest of the United States, lay beyond the scope of the recovery scheme, she says. Still, she acknowledges that both the plan and activism around Hawaiian independence are both “seeking a restoration of economic independence.”

Judging by the plan that independence can take many forms, one idea is to allot 20% of federal stimulus money to the Native Hawaiian community, which will benefit Native women, a particularly vulnerable group. Another is to increase women’s access to employment opportunities outside of tourism and commercial sex work. Above all, “feminist women’s leadership” needs to be at the forefront of recovery planning and implementation.

The recovery plan recognizes that Hawaiʻi is not a monolith.

Despite the plan’s specificity, it was never intended to be implemented to the letter of its current 23-page incarnation.

With all the agility of the U.S. Constitution, the recovery plan recognizes that Hawaiʻi is not a monolith. It is a highly diverse nation of seven inhabited islands where people of Native Hawaiian, Asian, and mixed-race ancestry together make up most of the population.

The feminist recovery plan is increasingly important as the number of COVID-19 cases grows in a majority of U.S. states. The plan has already started to influence state and county-level programs and legislation in Hawaiʻi.

The state Senate is considering designating $15 million for child care relief, which would allow child care businesses to open and caregivers to return to work, a main tenet of the feminist plan. The Recovery Team is still gathering and submitting testimony in support of the passing and adoption of a resolution in Maui County, intended to benefit the lives of women and girls on Maui, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi, and Kahoʻolawe islands.

Jabola-Carolus also says the state Department of Labor and Industrial Relations and the State Commission on the Status of Women are starting a jobs program to improve unemployed women’s access to green jobs and trade industries.

Inspired by these victories, the State Commission and local activists are continuing the conversation about how the recovery plan can best be interpreted and adapted in different localities for maximum impact.

“We’re still meeting every week and still doing events every week to talk about it,” Jabola-Carolus says. “[T]here’s lots of room for revisions, not just on policy but what programs and actions are needed and we’re doing that. So, it’s still very much alive…”

|

Ruth Terry

is an award-winning freelance journalist based in Istanbul, Turkey, who writes about everything from race to rollerskating.

|

|

Megan Wildhood

is a writer, speaker, and advocate for the marginalized. She is the author of the poetry collection Long Division.

|